Note: this site and the author does NOT have any financial relationship with the service provider being reviewed.

THREE POINT OVERVIEW:

1.) Hudson Labs is a finance-specific AI solution built to help public equity analysts extract information and data from company-provided sources with a high degree of accuracy and traceability (SEC filings, press releases, company presentations, conference calls).

2.) I found the accuracy of data and information retrieval to be high. Checking accuracy vs. underlying documents was made easier with well-designed citation features.

3.) Hudson Labs is not an end-to-end solution for investment analysis (nor does it claim to be). But it can help streamline part of an existing research process, especially as it relates to pulling and condensing unstructured quantitative and qualitative data.

INTRODUCTION:

This is the first of a two-part review on Hudson Labs.

Hudson Labs (“HL”) is an institutional-grade, finance-specific AI tool for financial analysis of US public companies. HL uses more than five proprietary LLMs trained on millions of pages of financial disclosures. So while HL does use OpenAI models for some language processing and generation, it is not a ChatGPT wrapper. HL’s main value proposition is handling high-precision finance tasks where hallucination and accuracy errors can be very costly.

This is a good area of focus. While there has been a lot of improvement across all of the general-purpose AI models this year, as I’ve written over the past month (see X post below), these models continue to struggle executing financial tasks related to retrieving and analyzing very specific information from reported financials. As of December 23, 2025, GPT 5.2, GPT 5.1, and Opus 4.5 score in the 53-57% range in terms of accuracy in these types of financial tasks according to the Vals AI benchmark, which is obviously a major issue for investment research purposes (and institutional adoption). It’s kind of hard for me to square these problems on basic analyst-level tasks with incessant posts claiming “Opus 4.5 is AGI” and “we need UBI now”, etc. - any time I look at these types of posts on X I can’t help but wonder if I am missing something.

So all that is to say, for finance-specific AI tools like Hudson Labs, focusing squarely on data/content retrieval and accuracy is a worthwhile pursuit, as this is a very apparent gap in the capabilities of otherwise very powerful general purpose models.

Before we move on to the actual review, lets go through what Hudson Labs covers and where it can fit into analyst workflows at a high level.

Hudson Labs covers all public US companies and 1,400+ ADRs. It’s core offering is its “Co-Analyst” feature, which allows users to prompt the system to gather and summarize data/information from company-provided sources (including SEC filings, press releases, investor presentations, and conference call/event transcripts). HL maintains an updated internal library of all these materials so no uploads are necessary (nor are uploaded files supported). The platform does include access to valuation multiples from S&P, but this valuation data exists in a separate tab from the Co-Analyst feature and to my knowledge cannot be pulled into the Co-Analyst interface for additional analysis. The bottom line is Hudson Labs is narrowly focused on processing company-provided sources without hallucination or data errors. At least for now, it leaves gathering and analyzing data from other information sources to the analyst.

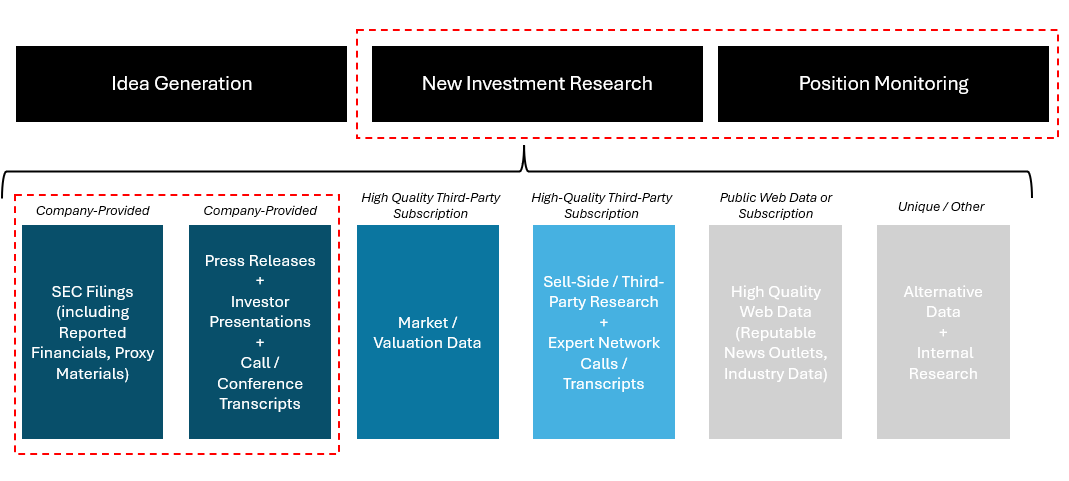

Figure 1: Hudson Labs augments analysis of “company-provided” information - the rest is left to the analyst to compile.

At a high level, If we categorize analyst workflows into i.) idea generation, ii.) new investment research, and iii.) position monitoring, I would say Hudson Labs supports mostly the latter two. Of course, there are overlaps and the platform can be useful for idea generation as well, but as of today it does not have broad screening features and to me is more of a tool for getting up to speed and digging into one specific name at a time. Building a screening tool on top of Hudson Labs’ infrastructure would be an interesting feature that I’ll provide some thoughts on in the second review.

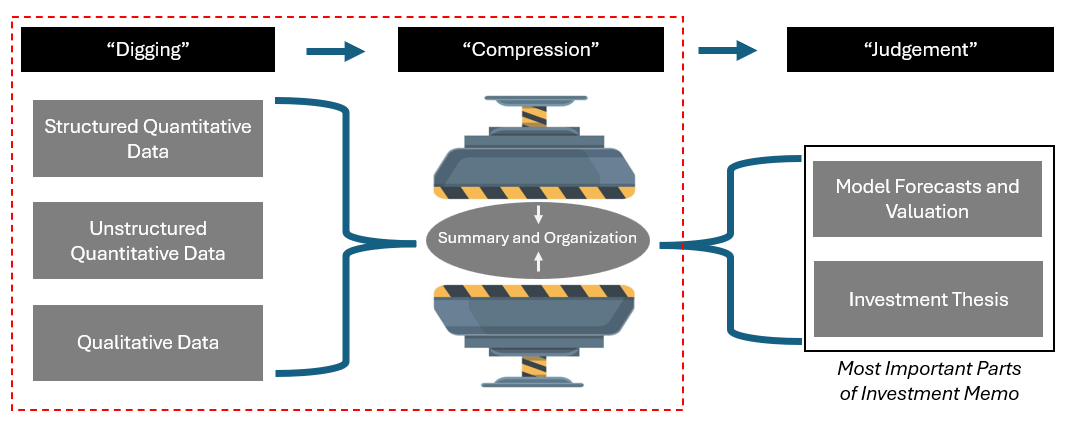

In my mind, most of the work a buyside analyst does (no matter which workflow category) can be dissected into a three part process - digging, compression, and judgement. Digging involves finding and pulling the relevant data/info - from structured quantitative (ie. financial tables), unstructured quantitative (ie. KPI’s within sentences in a press release), and qualitative sources (ie. management comments on a conference call). Compression involves squeezing that data by summarizing/organizing it into a usable format (either in a model or summary notes) to be processed in the final stage of the process, judgement. Judgement involves assessing and weighing all of the compressed information to create model forecasts, valuation analysis, and an investment thesis (all of which are key parts of a final investment memo/recommendation).

Figure 2: Hudson Labs focusses on the “digging” and “compression" stages of analyst work, leaving the rest to the analyst. I feel as though many bad experiences with AI are labeled as problems in the “compression” or “judgement” stages, but to me it seems many problems originate in the “digging” stage where incorrect data is retrieved.

Hudson Labs provides efficiencies in the digging and compression stages, especially as it relates to unstructured quantitative and qualitative data that is harder to organize into takeaways than just pulling financials into a model. I feel like every analyst knows that reading four earnings transcripts and quickly summarizing them into key takeaways is harder than it looks.

Hudson Labs picked a good name for their core offering (“Co-Analyst”), because it does not eliminate the need for analyst work or human judgement, but can retrieve and compress relevant info to get an analyst across the finish line faster. If getting up to speed on a name involves reviewing the latest 10-Q and 10-K, the past year of earnings/event transcripts, the past year of earnings decks, and the latest investor day deck, and then compressing this information into notes and a high-level model, a tool like Hudson Labs can clearly provide efficiency gains. Especially during a 1-2 day “initial look” for a new name, where stakes are still relatively low and you are just trying to get to a decision whether to “do more work” or “put it in the too hard/too risky/too expensive/does not fit mandate pile”, it’s easy to see how this type of tool can get you there faster.

REVIEW OF RESULTS:

Hudson Labs’ core Co-Analyst offering has a prompt/query library (ie. commonly used prompts that can be used to get a business overview, review of the latest earnings release, evaluate management compensation, etc.) or can be prompted manually by the user. I tested both the pre-set and custom prompts.

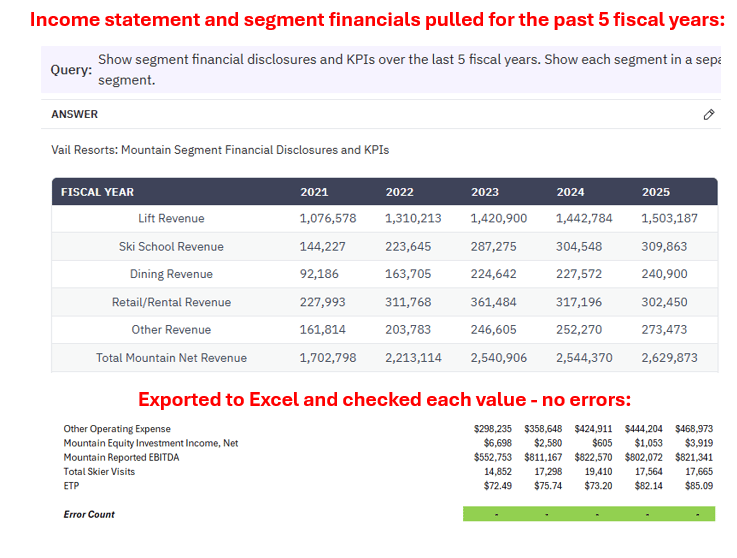

First, I tested the Co-Analyst’s ability to pull historical income statement and annual segment financials/KPIs as reported in the last 5 fiscal years (using Vail ($MTN) as an example once again). I found that my prompts had to be very clear that I wanted the layout to be exactly as reported in the financials, with each segment shown separately, in order to ensure that all disclosed line items were pulled (not just summary line items like total revenue and EBITDA by segment). After adjusting my prompt, the end result was that all numbers were pulled correctly for both the income statement and segment financials - I checked all 360 cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Historical financials were pulled with no errors in all 380 cells

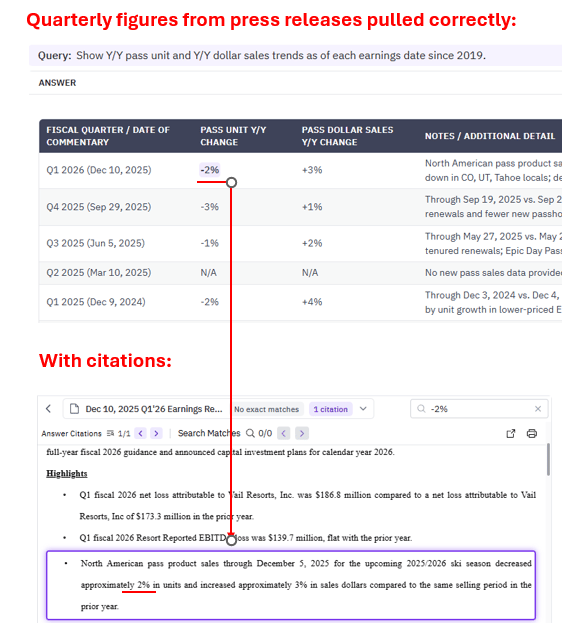

Next, I wanted to test the Co-Analyst’s ability to pull unstructured data, which takes the most manual effort to compile. In the case of Vail, management reports ski pass sales trends for the upcoming season (unit and dollar sales trends Y/Y) along with its earnings releases, but this information is usually included in sentence form (unstructured quantitative data). The data is also reported as of a date near the earnings date, rather than as of the fiscal quarter end, so to get accurate results I had to be specific in my prompt to ask for sales trends as of each earnings date rather than as of each quarter (I found the Co-Analyst would get confused if I asked for trends as of each fiscal quarter, since the trends reported along with fiscal Q1 earnings for example are as of a date that is post-quarter-end and technically within fiscal Q2). Once again, with the right prompt all numbers were pulled correctly for the past 20 quarters. It’s easy to see the efficiency gains here - instead of locating a specific sentence in 20 different press releases and putting all of the data in a table, I can pull all of these data points in a few seconds (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Unstructured quantitative data pulled quarterly was correct, with citations to check source documents quickly

The citation feature has a nice interface, where all data can be cited with a right click, and is shown in the source document in a panel on the right-hand side of the screen. In this example, you can see that we can trace where the -2% number in the Q1 2026 press release comes from. (We would note though that sometimes the citation functionality is sometimes glitchy in large data sets even though underlying data is correct).

The Co-Analyst is also good for getting a set of summary business overview notes from the source documents, and this summary information is, once again, traceable via the citation feature (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The Co-Analyst condenses qualitative information into notes with citations

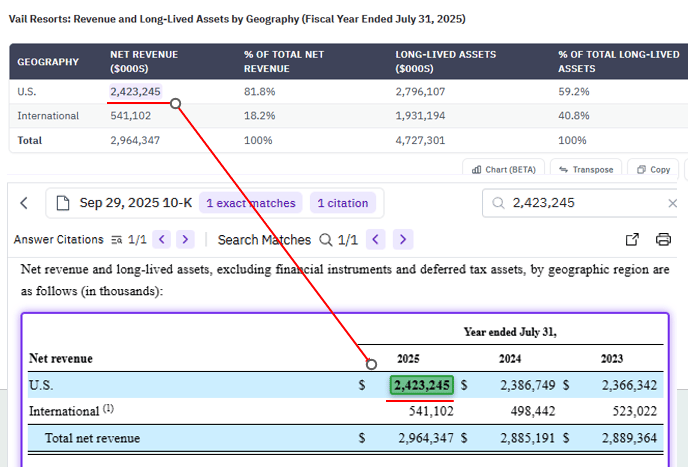

In the early stages of the research process, getting a quick run-down of the contribution by segment and geographic region is also helpful (Figure 6) - I was using the citation feature every time for peace of mind.

Figure 6: Geographic breakdown pulled from latest 10-K

Another prompt that might be useful in getting up to speed on recent capital allocation trends, is asking for a summary of acquisitions made over the past 5 years (Figure 7). You can see part of the citation panel on the right-hand side which is open at the same time right beside the outputs - it’s hard to fit the full screen into this write-up format, so we screenshot and cut citation boxes in all of the examples above.

Figure 7: Acquisition summary, all information pulled from various 10-Ks. Citation panel is partially visible on the right.

Below is part of a run-down of the major operational catalysts or initiatives over the past two quarters (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Hudson Labs can pull together a list of key current operational initiatives that may serve as catalysts.

Another useful prompt, was to get a summary of the top points of focus from analyst questions on the last several earnings calls (Figure 9) - as you can see, in the case of Vail, issues with respect to lift ticket price vs. volume impact from recent discounting strategies and dividend coverage risks were brought to light - both of these issues (along with pass volume trends) are key in the debate around Vail, and were easily brought to my attention within the first few minutes of research.

Figure 9: Summary of areas of focus across sell-side analyst questions on recent earnings calls can bring key issues to light quickly.

And of course, these question themes are traceable so I used the citation feature to read the management responses to these questions (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Tracing earnings call themes allows you to read full questions and management responses

When using Hudson Labs, an analyst can have confidence in the information sources and use citation features to check the work. Will the responses to these prompts cover 100% of the issues affecting the business/stock at any one time? No (especially if not mentioned in source materials) - but if this tool can help you get 50-80% of the way there very quickly, that’s valuable.

Note that in addition to the above functions, Hudson Labs can provide earnings summaries, guidance summaries, and other outputs that can help an analyst streamline their process. I haven’t tried all of the functions yet - this piece is meant to give you a flavor of what is possible on the platform.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

Strengths:

1.) Hudson Labs is focused on an area of financial analysis where general purpose models are lacking. A tool with a narrow focus on pulling information without errors only from high quality, company-provided sources will be valuable as long as general purpose models and other tools with a broader scope continue to struggle in this area.

2.) The content library is automatically updated with no user input required. While a tool like NotebookLM should also have lower levels or errors/hallucinations than general purpose models (and provides citations to source documents), uploading tens or hundreds of different documents manually to NotebookLM would be very time consuming and would eat into the efficiency gains (though I do want to test how NotebookLM would perform at many of the tasks I’ve covered here).

3.) Citation features are important and, in this case, designed nicely. The one click citation that brings you directly to the source information within the same visual window is key. In some of the modeling tools that I’ve written reviews on recently, citation features just tell you the page of a 10-K where something was pulled from - but if you have to manually pull up a 10-K and Ctrl+F to search for information, the verification process is much more tedious.

Weaknesses/Considerations:

1.) The narrow focus of the tool means that information that is not included in the content library is not taken into account in its outputs. Information from other sources such as sell-side research, expert network transcripts, market/valuation data sets, and internal research are not taken into account within the Co-Analyst and cannot be uploaded.

2.) The Co-Analyst does not handle complex financial calculations if they are not explicitly reported. For example, if you ask for annual levered free cash flow and “free cash flow” is not a specifically reported figure, the Co-Analyst will not return an answer (at least in my test runs). So while you can use Hudson Labs to pull the underlying figures from the financials to calculate FCF, the calculations would have to be done manually.

3.) Is it 100% perfect? No, but no tool is and further improvements are likely. For example, the citation interface can be glitchy in large data sets (even where correct data is pulled, sometimes the citation feature lags). There are also limitations in the amount of documents that can be processed at one time for a single prompt - as of December 2025, Hudson Labs has said its limits include processing up to 6 10-Ks or 20 press releases at a time (splitting up work between prompts can be a work-around).

CONCLUSION AND NEXT STEPS:

If you are a public equity investor, I think Hudson Labs is a platform that is worth trying within your research process. Saving a set of prompts that you punch into the platform to get up to speed on a name using information only from company-provided sources can form an efficient and low-error AI-augmented process without significant implementation or learning hurdles.

Hudson Labs has institutional and single-seat subscription plans (here), so its a viable option for small teams and even individuals.

I will be posting a second review on Hudson Labs with a few more features/functions that I think are useful, as well as with some thoughts on how screening tools built on top of some of the functionality may create interesting new ways to identify potential opportunities in the near future (ie. AI enhancing creativity vs. only efficiency).

Thanks for reading. If you have any questions or suggestions for future reviews, please reach out!